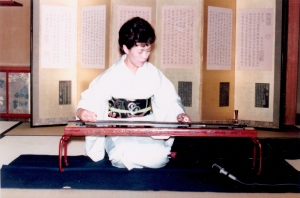

In 1987 I had the great fortune to be a student with Park Gui Hee 박귀희, the first person to hold the position as Important Intangible Cultural Property No. 23 for kayageum sanjo and byeongchang. Kayageum is a long zither with twelve silk strings and movable bridges. Traditionally, the instrument is plucked with the fingers of the right hand while the sound is manipulated by pressing the strings to the left of the bridges with the left hand. Sanjo is a solo improvisational form, while byeongchang is a vocal form accompanied by kayageum.

As I explained in my previous blog on Korean shijo, Kim Duk Soo, the leader of Samul Nori introduced me to Park Gui Hee while I was in Korea between concerts on an Asian tour. I was already playing the Chinese zheng, the parent of the Asian long zithers, so Duk Soo thought this would be a good fit.

The daily routine at Park Gui Hee’s studio was for the students to start practicing well before she arrived. Once there she would spend one on one time with selected students working on the details of the piece they were learning. This was the traditional method of aural/oral transmission, there was no written music used. The teacher played, the students copied and memorized. Learning a piece with this method takes time. Rather than just learning what note to play, every aspect of each note is learned all at once, including its timbre, timing, expression, dynamic, and inner motivation. The students have to listen with every aspect of their being to understand the depth and meaning of the music, and to fully commit to its expression. This was very challenging.

The daily routine at Park Gui Hee’s studio was for the students to start practicing well before she arrived. Once there she would spend one on one time with selected students working on the details of the piece they were learning. This was the traditional method of aural/oral transmission, there was no written music used. The teacher played, the students copied and memorized. Learning a piece with this method takes time. Rather than just learning what note to play, every aspect of each note is learned all at once, including its timbre, timing, expression, dynamic, and inner motivation. The students have to listen with every aspect of their being to understand the depth and meaning of the music, and to fully commit to its expression. This was very challenging.

On my first day as a junior student I was introduced to Park Gui Hee, and then explained who I was and what I wanted to achieve. After some discussion I was introduced to a senior student who was to teach me the fundamentals. I was shown the basic right hand picking techniques, which were not that different from what I knew on the zheng. Next came the most idiosyncratic right hand technique for the kayageum. The index finger plucks a note and then the same string is flicked with the nail of the middle finger and index finger in rapid succession. This is accomplished by tucking the index finger behind the thumb as if to flick a piece of dust, and then the middle tucked behind the index in the same manner. Performed properly this technique creates a roll or type of tremolo that can vary in speed and dynamic.

My instructor demonstrated this technique to me and then went through it slowly so I understood it. It was very challenging, as I had never used my fingers in that way before. I fumbled terribly. After a while of my struggle to get a handle on this technique, my instructor stopped me and said, “This is an essential technique for the kayageum and it takes well over a year to learn. Without it, we cannot teach you more. So I will teach you a basic piece for the rest of today, but your lessons are finished. You are welcome to return to listen at any time.” That was on a Friday.

I decided that I didn’t want my lessons to end, so I spent every waking moment of the weekend practicing this essential right hand technique. That meant I ate with my left hand while practicing the technique, a somewhat messy affair at first that got better. I practiced while reading; I practiced while taking buses, grocery shopping, and even visiting friends, pretended I had some kind of nervous tick. Gradually, I began to conquer the technique and by Sunday night could perform it on the kayageum. Monday morning I arrived back at the studio and sat down in front of my student teacher. She looked at me questioningly and I put a kayageum in my lap and demonstrated my newly mastered technique. Her jaw dropped and she screamed! All the other students came rushing over and saw my doing the technique and were as equally shocked, “That’s not possible!” they remarked. “How did you do that? It took me two years to learn that.” I explained that I was a professional musician and practiced non-stop.

Hearing of this Park Gui Hee reconvened my lessons, and I was then taken through the left hand techniques. Korean music utilizes a wide variety of vibrato, many of which are not mere ornamentation but fundamental notes in constant motion. Korean folk music uses a modal structure called tori, which designates the five main tones of the scale. Often one or two of these is always played with a moderate or very deep vibrato. Then another note in the mode will be a falling note that descends from the original pitch, and is always played as such. These moving pitches all have an emotional characteristic that is must be expressed properly and is often the subject of work with the teacher.

I met with Park Gui Hee once a week to demonstrate my progress and she would correct some things and then give my student teacher detailed instructions in what to do for my next lessons. The learning curve was very high and the schedule grueling. I remember Park Gui Hee working with one student for a number of hours on just two lyrics of a piece, both of which were “sarang,” meaning love. The first rose slightly expressing the joy of love, while the second descended with a complex convoluted vibrato, voicing the pain of lost love. The student could easily reproduce the first lyric, but the second the teacher was very fussy about, with the student copying the teacher’s example repeatedly for hours on end. This student worked only on these two sung words for months, which was the level of commitment to detail demanded in the studio.

Park Gui Hee lived close to the studio in an old Korean courtyard Manor. She lived in a large multi-storied house in the middle of the square courtyard surrounded by a wall on all four sides, with a large gate on the southeast corner. The inside of the walls were lined with small sleeping rooms on three sides, and the kitchen and bathing rooms on the south end. Except for the house, the rest of the compound was turned into a yogwan, a Korean traditional style B&B. I lived in one of the rooms. The rooms lining the wall varied in size, but the majority of rooms were only large enough for two people to sleep on the multi-layered varnished paper floor. Each had sliding paper doors with a small entrance way. There were no chairs only cushions on the floor, the bedding was laid out at night and rolled up in the morning. The rooms were breezy, which was a good thing as they were heated with coal fired hot water heaters in the floor, and many people died each year from coal gas seeping into the rooms. Although the grounds were totally surrounded by city buildings the walls blocked a large amount of city sounds, and so the yogwan was a very peaceful place to stay.

Park Gui Hee gave private lessons in her house so every evening the courtyard was filled with the sounds of kayageum byeongchang. I spent from six to eight hours a day taking lessons and practicing in the studio, then came back to my small room to practice a few more hours, while listening to the lessons coming through the walls every evening. This constant exposure felt like a total immersion in the genre, cementing the music deep into my soul. Listening constantly to soaring voices sitting on the razor’s edge between a cry of pain and a cry of joy, performed with such commitment and passion, was an education unlike any I had ever experienced before. It was like being in a constant state of ecstasy, so much so that I often had to improvise quietly along with the lessons next door to give voice to my own ecstatic expression.

I felt like I was in two worlds. I would walk out the gate into the modern chaos of Seoul. This was the time a student unrest, so there was often a lot of tear gas in the air, and I learned to avoid approaching student riots by ducking into a subway station and taking the train back behind the riot, to find shopkeepers opening their shops and sweeping bricks and stones away from their doors. I would return to my yogwan and enter old Korea again, sit on the floor of my room listening to the lesson next door while eating an evening meal of rice, vegetable and kimchi, and a few hours of practice before sleep.

My time in Korea was too short, as I would have needed years to live and study all that I wanted to on the kayageum, and life didn’t take me in that direction. However, what I did learn was profound. Korean music is a balance of opposites and extremes: heaven and earth, male and female, joy and pain, tradition and innovation, silence and sound, Confucianism and shamanism, composition and improvisation, order and chaos. Park Gui Hee’s lessons pushed me deeper into my musical soul, freeing me to create with all of my being at every moment. As I continued to study Korean music I have found a deeper balance within myself, allowing me to express my wildest passions while maintaining a calm still centre.

Korean traditional music is in my opinion one of the world’s richest musical treasures, and essential study for anyone forging new directions in creative music and self-expression. I highly recommend it. It can change your life.

© R. Raine-Reusch 2014

k to attend the first traditional naming ceremony to take place in many years. I was hoping I might hear and be able to record some traditional music there.

k to attend the first traditional naming ceremony to take place in many years. I was hoping I might hear and be able to record some traditional music there.

of the circle, but I quickly pulled him in line with us and said to him “Pema, you are one of us.”

of the circle, but I quickly pulled him in line with us and said to him “Pema, you are one of us.”